Angles in a Landscape

Learning the concepts

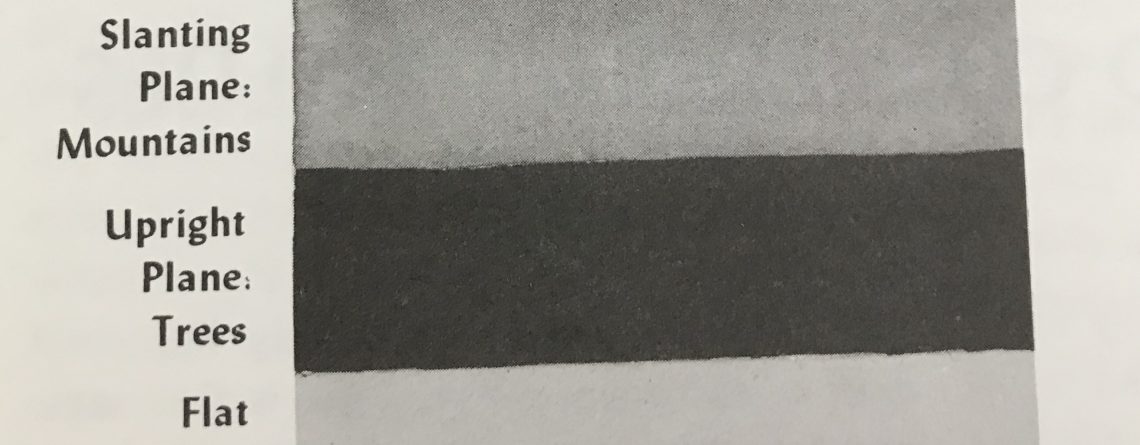

An important concept in painting landscapes is good design. According to John F. Carlson, in order to achieve this, there should be four values in the painting. These values, in turn, influence three planes: the horizontal, the angles, and the vertical. In each plane there are masses such as the ground (horizontal), a hill, (angles) and a tree (vertical), whose values are assigned based on their levels of exposure to light. The artist’s job is to create shapes out of these masses based on their value.

In his book, Carlson’s Guide to Landscape Painting, Carlson calls this process “The Theory of Angles.” The first value is the sky, which is the source of light, and therefore always the lightest value in the landscape, whether on a clear blue day or an overcast grey day. The next value is the ground, which receives the most light from the sky. The third value is the slanting plane, such as hills or mountains, which have a semi-dark value somewhere between that of the trees and the ground. The darkest value are the trees because they are perpendicular to the ground.

Because the masses in the landscape may possess some variation in value, they can appear to straddle two planes. For example, there might be light on the trees, making their value similar to that of the meadow. However, these seeming half-steps of value within each large plane are where they belong–light falling on a tree still belongs to the vertical plane.

Practicing

Plein air painting is direct painting from the scenery that surrounds the artist. One is immersed in and absorbed by the beauty. Painting the elements found in nature helps develop visual acuity; observing rock formations, the clouds, the sea, the mountains, tree formations, etc., are vital to the study of landscape painting. Many landscape artists do small sketches on location and bring them to the studio. This enables them to first analyze the light source and break down the value of the planes. Therefore, it is good practice to keep a sketch book on hand. A sketch can be turned into a painting in the studio.

Helpful hints

Paintings are not usually poor because they lack detail or subject matter, but rather the opposite. Bad paintings are usually so overloaded with useless details that the essentials are obliterated. To avoid this, be sure that the details within the elements conform to their given values within each plane or the painting can become visually cluttered.

As always, there are some exceptions to the theory of angles. The student, after understanding the general rule, will be better equipped to make the necessary adjustments. The habit of analyzing the weight or value of any mass will prove invaluable and prepare the artist for unexpected and unusual circumstances.

Recommended Reading

- Edgar Payne, Composition of Outdoor Painting

- John F. Carlson, Carlson’s Guide to Landscape Painting

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.